Is that right?

Most local birders catch up with the bird when an individual takes a liking to the ready food source held within the Chatham Maritime basins, suitably served in a decent depth of water all day long. Up to the mid-eighties these basins were out of bounds in the old Chatham Dockyard Naval base, and Oliver was published in 1991.

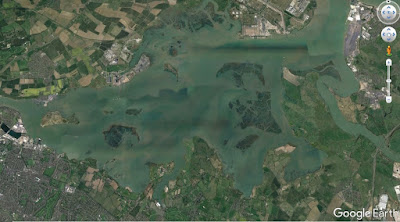

Are there still Shags to be found on the tideway? Simple answer, yes. Thanks to being in the position to visit the estuary almost daily, that can immediately be revised to an annual visitor. To find your own, once again you have to think about food and roosting.

The old records point to deeper creeks, with no mention of tideway state when seen- Motney (so, Bartlett Creek), Greenborough/Stangate Creek and Kingsnorth (Damhead Creek, Long Reach). The comments under Cormorants regarding prey concentration during the running of the tide apply equally well here: a bird can be found actively feeding, a bird might be found hauled out on the rockier flats over the lower tide. 'Might', because they can often choose to use their favoured high tide roost, or go elsewhere to continue feeding.

Safe roosting

The Kent Bird Report of 1996 draws a conclusion that four Shags visiting the basins were the same as four seen roosting some four and a half kilometres away. Fair conclusion? Never seen moving to and fro, but much of that flightline is underwatched. The roost, the Oakham jetty at Kingsnorth, is one of the few Shag-friendly roost sites on the Medway. They do not join the Cormorants a short distance east on the crumbling metal framework of the Bee Ness Jetty; Kingsnorth is more substantial, designed to take traffic and made of concrete with, thanks to the support design, a series of suitable roost ledges tucked just under the roadway. Roosting birds can be well hidden, and were often only found by leaning out and scanning a long way back along the jetty.

In recent years when asked why a basin bird might be missing, I have suggested only really down to lure of easier concentrated fishing in the creeks and that a middle of the day search, especially around the high tide, is the best way of guaranteeing a good chance to tick-and-run. Over the tide, even if well-fed and looking to day-roost, buoys on the calmer waters right next to snackfood beat returning to the main roost.

Occurrence

It is fair to say Bill Jones has seen more Medway Shags than any other birder, thanks to his years as Environmental Initiatives Officer at Kingsnorth Power Station. His assessment of Shag timings for the Medway differs from that published- most have occurred around Oakham/Kingsnorth in early-/mid-spring, notmid- winter.

With most observers only having Shag on their 'radar' in winter, just as there are fewer birders on the Medway in the spring, there are fewer searching for them (sightings are often far from the shoreline). Even so there are March, April sightings popping up in the records, including from recent bird cruises on mid-estuary.

As discussed in several old blogposts, this estuary is 'non-coastal', so 'migration' often go undetected- late autumn movements such as those recorded from time to time on the north Kent coast do not happen.

Taking the North Kent Marshes as a whole, Shags have turned up in every month of the year (an exceptional story follows below) so they should never really be off a birder's radar. They do vary in numbers from year-to-year, which is most likely down to food abundance elsewhere; many do not bother to move that far from breeding areas- they just need to move on to the next easy fishing.

Origins

Ringing recoveries trace many Kent birds back to coastal eastern Scotland. Fewer Farne Island birds move as far- the Scots leapfrog them. Perhaps island fishing is better? Certainly onshore winds make fishing harder, and prolonged strong easterlies force Shags along the coastlines.

They do not come from the continent in any number. As per Cormorant, they do not like leaving sight of land- they need to haul out to dry off, so better to locate new feeding close to shore.

Are we really seeing adults?

In describing plumages some forty years ago, the first volume of Birds of the Western Palearctic used a phrase now out of favour- 'first adult plumage'.

Shags usually do not breed until their fourth year. Now another Shags can tell an age easily, but can struggle after the first couple of immature years. The problem, left out of many of the guide books, is the three year olds. As BWP went on to explain this first adult plumage is "acquired gradually between second and third autumn; some specimens, however, like adult in March of third calendar year..."

So, a third winter youngster, one not set to try breeding until the spring, may well look like an adult.

To ramp up the problem, the recent 'Identification of European Non-passerines' by Baker, seems to say this is a real problem. To quote, "3w- most not ageable but a small percentage of birds (2% of males, 4% of females retain (an immature type) outermost primary until summer of fourth calendar year."

So, us southern softies, with our limited experience of Shags, and certainly not that many close up views, have a habit of going and claiming 'adults' when we often might have no way of ruling out a sub-adult (and probably never consider that age).

Does this really matter? Well, if you want ot publish official records as adults, yes. Philopatry. In rough terms, in many non-passerines long-lived species take several years to mature; they might not migrate routinely during their lifetimes. A successful adult will often winter close to the breeding grounds if food is available. Out-competed, outranked youngsters have to move. They may stay at a chosen wintering site first year, they might venture closer to natal breeding grounds in second summer and they might even stop awhile at the start of the third breeding season, but they are recognisable to adults and usually not taken on as 'risky breeding stock' unless, say, something has happened to a chosen mature partner just as the colony reassembles.

In Shags, variability in feeding can lead to varying numbers of adults moving more often in some winters, but for anyone trying to study Shags in the south-east any apparent increase in adult numbers does not reflect any real change in adult patterns- they are still not likely to go further than they need to. But read the bird reports and it seems adults are visiting. It is just as likely to be immature birds finding our recovering waters more suitable again. Ringing recoveries do show that adults are appearing, but we cannot presume adulthood as easily as we do.

Chatting with Bill Jones on the Kingsnorth Shags, he certainly wondered if any birds hanging on into spring on his artificial ledges along Oakham jetty signalled older youngsters with increasing hormones. Could loitering third summer birds ever lead to a claim of possible breeding?

The Kemsley young 'uns

A nice published history from older Kent Bird Reports from the neighbouring Swale:

1991- "two wintering in Ridham Dock in the last quarter"

1992- "in the north three first year birds were resident on the Swale at Kemsley to June, with two second years then remaining to year end"

1993- the two remained at Kemsley throughout the year and were joined by four others from Nov 18th to 28th"

1994- birds were present at Kemsley... for most of the year, with numbers increasing from one in January to six by Feb 12th, with peaks of three in March, six in April and four during July to October"

Now that is something- a great chance to have noted all these different Shag plumages through the years here in north Kent; juvenile/first winter changing to the paler first summer to the off-adult second winter and then into the more confusing second summer. I'd opine there'll never be anything as rare and exciting as that around that part of the Swale- though I'm sure others would disagree with that this very week.

Okay, so I might have to let that slip. But do expect a few hard questions if you try to tell me a Shag on view on the basins is an adult.