"Common and widespread resident, passage migrant and winter visitor."

And I used to believe that. Along come the textbooks where such statements get repeated:

"..large numbers of the nominate race from northeastern Europe occur here on migration and in winter.." ('Birds in England', Brown and Grice)

Trouble is, when you start to read more analytical texts, firm evidence for winter visitors in any number becomes a touch wobbly.

"Ring-recoveries support the idea that a few (nominate race) rubecula winter in Britain and Ireland.."(Migration Atlas, Wernham et al)

So. Large numbers? Or a few?

So. Large numbers? Or a few?

Of course, I always used to believe the 'big numbers overwinter'. I used to go do talks on garden birds, on migration, for a past employer, to local WIs and the like, and spend my time spinning charming little tales that 'their' Robin they see in the back garden each winter probably had a Polish accent. Argh! Now? I believe this to be well off the mark.

I'll try to explain, and as I keep saying, I'm no scientist, but.. (Open minds everybody!)

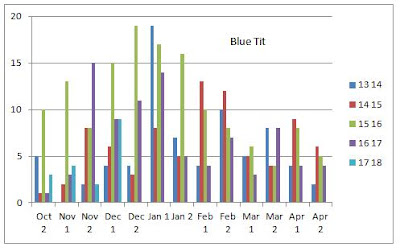

A lot of autumn movement there.

Now, lets overlay (well, underlay) the main migration periods, based on the excellent 'Migration Atlas' and 'Birds of the Western Palearctic:

Now, lets overlay (well, underlay) the main migration periods, based on the excellent 'Migration Atlas' and 'Birds of the Western Palearctic:

Suddenly the spring encounters show up as being after the supposed peak passage period through the UK. Just a handful can be felt to have been at their overwintering areas- the others more likely birds that have wintered further south in Europe. And probable that the vast majority of the autumn passage Robins passing through the south-east of England are not now staying in Blighty, they're making for Iberia and the like.

Another small consideration. The concept that not all coastal Robin 'influxes' will be continentals. Let's alter the charts further, by adding in moult finishing periods. For adult Robins, depending on when breeding finishes, up to end September (dark blue), their later broods ending post-juvenile moult as late as mid September (light blue). Most longer distance dispersal of 'resident' UK Robins happens at this end of the moult period. Adults have territories to defend, first, second broods have had to find somewhere to defend and now any third broods, and the (small!) number of overwintering continentals add to the disputes. Most Robins might not go far, less than five kilometres for a winter territory, but a number now wander a little further afield. In a county with northern, eastern and southern coastlines quite a few could pitch up on the coast. Why if a ringer looks back through their records, they might find a lot of local 'resident' Robins get ringed in October.

Another small consideration. The concept that not all coastal Robin 'influxes' will be continentals. Let's alter the charts further, by adding in moult finishing periods. For adult Robins, depending on when breeding finishes, up to end September (dark blue), their later broods ending post-juvenile moult as late as mid September (light blue). Most longer distance dispersal of 'resident' UK Robins happens at this end of the moult period. Adults have territories to defend, first, second broods have had to find somewhere to defend and now any third broods, and the (small!) number of overwintering continentals add to the disputes. Most Robins might not go far, less than five kilometres for a winter territory, but a number now wander a little further afield. In a county with northern, eastern and southern coastlines quite a few could pitch up on the coast. Why if a ringer looks back through their records, they might find a lot of local 'resident' Robins get ringed in October.

We want these Robins we see in the migration period to be migrants. We want Robins fighting on the seawalls in mid-September to have crossed the North Sea. Our mindset is skewed towards it. Here, we go down the estuary to Horrid Hill, find a few extra about and think 'Polish', when more likely both singing with a Medway Towns accent; our impoverished gardens can only hold so many, and these youngsters have been kicked out. Ah well, a man can but dream.. Dream all you want, but those Robins on Horrid will have mainly come from points north of Twydall.

In that same BTO report is a tally of Robin encounters, based on UK (by counties) and overseas (by country):

Now, for all those s-e birders who get excited by falls at the likes of Spurn, and moan 'why don't we get the same here?', I'll point out, once again, Spurn might as well be another country, we're so different. Look closely, we encounter very few Robins from other counties beyond a line from the Wash to the Bristol Channel (just three from east Yorkshire). We don't register as being on that North Sea route. Even when we hope for birds to filter down, migrants arriving north of the Wash have little reason to filter via Kent because they can go due south or south-southwest as they leave, or just make the short flight over us and the Channel straight back onto the continent than touch down again in Blighty.

And we mustn't draw straight lines when looking at ringing data. Those Scandinavians we've had in Kent will have, statistically speaking, most likely used the main passerine flyway of southern Scandinavia to Denmark to Low Countries.

Spurn? Forget 'em. Passage migrants through Kent are often using a completely different flyway. (Trust me, just checked that BTO site again; in comparison to us E Yorks has Robin just one exchange with Poland, none with Russia, none with the Baltic States.)

You catch a ringed bird here in Kent, the ring might say 'Norway' but you can't claim a direct flight. So why do some counties nowadays report ringing encounters as 'origin' and destination' in their annual reports? They're usually neither. Unless ringed as pulli in nest, you can't claim an exact origin. Any juvenile/adult might have been ringed some distance from their true origin. And you must appreciate you can't claim UK as the destination for vast majority of foreign ringed birds encountered here. Just as likely a stopover. These are the sort of well-intended errors that lead to such urban myths as large numbers of wintering conti Robins in the first place.

(All why I'm hoping to live long enough to see the European Migration Atlas published. Bring it on.)

So how would I describe Robins?

We do get a small number of coming in from continental Europe to overwinter. Really not enough encounters yet to confirm origins, yet alone prove intra-seasonal European arrivals such as on a 'cold weather movement'. Nowadays, if you tell me you have 'your' Robin comes to your garden just for a few months each winter, and that it has an eastern European accent I'll say more likely it speaks fluent estuary English. And it'll be a new bird each year, a youngster, that if disappears by February, it's not made it. Roughly, three out of four youngsters won't make it to breeding. But if it disappears after that, it's gone to look for a half-decent territory because your garden really isn't quite good enough. Your neighbour's artificial grass and paved front garden really aren't helping town Robins.

Now that's a bit more like the real picture.

Oh, and let's knock 'in the field' claims of Conti Robins into shape. Gurus like the great Chris Mead spent time poring over skins at British Museum, ringed tons in the field, and came to the conclusion the plumage differences are slight and on a spectrum; even if you've just seen a couple of dozen closely in the past half-hour, you'll as likely not be able to correctly claim a nominate race Robin. So, best treat majority of in field 'conti' claims as unproven, along with a lot of in-hand as well. They *might* be, but more likely not. We like to see what we want to see.

There's a lot more evidence reflected in ringing papers; things like studies of passage migrants holding temporary feeding territories whilst refueling, and the suchlike. But you're safe for now, I'll save them for chats in the field when I need to bore someone..

In that same BTO report is a tally of Robin encounters, based on UK (by counties) and overseas (by country):

Now, for all those s-e birders who get excited by falls at the likes of Spurn, and moan 'why don't we get the same here?', I'll point out, once again, Spurn might as well be another country, we're so different. Look closely, we encounter very few Robins from other counties beyond a line from the Wash to the Bristol Channel (just three from east Yorkshire). We don't register as being on that North Sea route. Even when we hope for birds to filter down, migrants arriving north of the Wash have little reason to filter via Kent because they can go due south or south-southwest as they leave, or just make the short flight over us and the Channel straight back onto the continent than touch down again in Blighty.

And we mustn't draw straight lines when looking at ringing data. Those Scandinavians we've had in Kent will have, statistically speaking, most likely used the main passerine flyway of southern Scandinavia to Denmark to Low Countries.

Spurn? Forget 'em. Passage migrants through Kent are often using a completely different flyway. (Trust me, just checked that BTO site again; in comparison to us E Yorks has Robin just one exchange with Poland, none with Russia, none with the Baltic States.)

You catch a ringed bird here in Kent, the ring might say 'Norway' but you can't claim a direct flight. So why do some counties nowadays report ringing encounters as 'origin' and destination' in their annual reports? They're usually neither. Unless ringed as pulli in nest, you can't claim an exact origin. Any juvenile/adult might have been ringed some distance from their true origin. And you must appreciate you can't claim UK as the destination for vast majority of foreign ringed birds encountered here. Just as likely a stopover. These are the sort of well-intended errors that lead to such urban myths as large numbers of wintering conti Robins in the first place.

(All why I'm hoping to live long enough to see the European Migration Atlas published. Bring it on.)

So how would I describe Robins?

We do get a small number of coming in from continental Europe to overwinter. Really not enough encounters yet to confirm origins, yet alone prove intra-seasonal European arrivals such as on a 'cold weather movement'. Nowadays, if you tell me you have 'your' Robin comes to your garden just for a few months each winter, and that it has an eastern European accent I'll say more likely it speaks fluent estuary English. And it'll be a new bird each year, a youngster, that if disappears by February, it's not made it. Roughly, three out of four youngsters won't make it to breeding. But if it disappears after that, it's gone to look for a half-decent territory because your garden really isn't quite good enough. Your neighbour's artificial grass and paved front garden really aren't helping town Robins.

Now that's a bit more like the real picture.

Oh, and let's knock 'in the field' claims of Conti Robins into shape. Gurus like the great Chris Mead spent time poring over skins at British Museum, ringed tons in the field, and came to the conclusion the plumage differences are slight and on a spectrum; even if you've just seen a couple of dozen closely in the past half-hour, you'll as likely not be able to correctly claim a nominate race Robin. So, best treat majority of in field 'conti' claims as unproven, along with a lot of in-hand as well. They *might* be, but more likely not. We like to see what we want to see.

There's a lot more evidence reflected in ringing papers; things like studies of passage migrants holding temporary feeding territories whilst refueling, and the suchlike. But you're safe for now, I'll save them for chats in the field when I need to bore someone..

------

PS for my BTO chums: that Kent summary, check those two Norwegian rings 956611 and AS956611- they're the same bird. You're welcome.