Rarities. Always get the blood coursing. Excitement levels high. Even when you know the biology of the Coccyzus family of Cuckoos from North America is such that they will not survive an Atlantic crossing you might still get so beside yourself you start tweeting 'Boom, mega lifer!' at seeing a moribund bird in the autumn. Such is birding.

Survival. Birds need everything to be just right. Our 'common' Cuckoo needs to do the same in the spring.

Many excited when they first make landfall here in the spring. Getting the first for the year used to be a 'boom! initials in the annual bird report moment.' Part of why we remember first dates more than main passage periods I guess. So when I received a direct message on twitter last night, with what I knew to be a bit of a loaded question, I deflected a tad.

"Do you think a Cuckoo is possible in Kent on March 11th?"

My reply: "What do Cuckoos eat?"

----------

Birding is full of statistics., the question was just the sort to tempt me. Even if I am a bear of little brain. As I joke with other ringers, I've tried reading Fowler and Cohen's 'Statistics for Ornithologists' several times, but crash and burn every time. Some stuff has stuck, not enough.

Birding is full of statistics. Not just mathematical stuff. Statistics is about finding ways of organising, summarising and describing quantifiable data. Statistics is also about making inferences and generalising that data. What works for one question isn't necessarily the best system for another. And it seems we're into that wonderful mindset of there only being one way to describe the average. Which there isn't.

There are three main averages.

Average mean. The one we are all familiar with. Easy to do. The arithmetical average of your dataset. Give something a numerical value, total them, and divide by the number of items. Boom.

But that figure is not necessarily the same as the middle value of the dataset.

And it may not be the most likely value.

Average median. The middle value. The best way to describe this is to steal the example in the book. You have a colony of Manx Shearwaters on a small island, and you are looking for the average distance the young travel. If you did it purely by, say, ringing recovery, and you have 50 birds recovered within ten miles of your island, and another one recovered waaaaay down in the South Atlantic then your average mean is going to be south of the equator- which of course it isn't. Sort them by value, you have 51 records, count through to number 26, and that's your modal value, right there.

Average modal. The value that you see the most often. For those Manxies, it could be there were twenty distances of 15 miles. Because that's how far it is to the next island colony, and birds are swapping; context is a wonderful thing.

Now, with us simple birders and first dates, we nearly always play with average means. Especially when it comes to first arrival dates of spring migrants. Our dataset is never always simple. What if we have an overwintering Lesser Whitethroat? Some would say you clearly need to leave it out the figures then, d'uh. We run into real problems with overwintering Blackcaps and Chiffchaffs, and we might have to choose a date of the first multiple coastal (presumed) arrival, or similar; we manipulate our data.

Now, you might think something as simple as Cuckoo could be easy to play with. Well, yes and no. BWP quotes a ringing recovery of a second-calendar year bird found in France March 5th. This was presumed to have been one of those wonderful exceptions, a bird that wintered in Europe (young Cuckoos in their first summer generally return a little later than adult birds). You wouldn't really want that messing up your averages, would you?

So, this Cuckoo debate I was being asked to comment on. Seems that there's been a multi-observer heard-only record for 11th of March this year. Good for them I say. I try never to say someone hasn't seen something.

Instead I had asked my correspondent "What do Cuckoos eat?"

-----------

Banging a mathematical value on a date is easy. January 1st =1, February 1st, 32, and so on. You can play with dates. Many birders are fascinated by first dates.

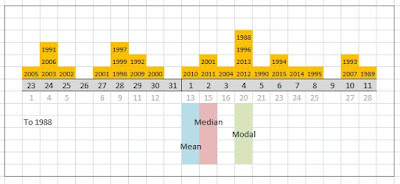

The full debate on this early sighting had focused on an average mean published in the County report, based on the last 15 years. The average mean was quoted as being 27th March, and was being queried by birders from other counties.

Now, for my blog, I went to the species descriptions in the annual bird reports for the dates. This is because the data had usually been reviewed by both the editor and the author for that species.

One big problem. The earliest date listed in that 15 year period under review in the debate was 13th March 2004. The Report actually had 3rd April in the body; the 13th appears in a 'first and last' table. 21 days out. That would throw things.

Your data has to be robust.

I'm not worried about which one is right at the moment, I want to focus on other things. I'll let others look into and confirm. I'll just take the species accounts dates for now.

One big problem. The earliest date listed in that 15 year period under review in the debate was 13th March 2004. The Report actually had 3rd April in the body; the 13th appears in a 'first and last' table. 21 days out. That would throw things.

Your data has to be robust.

I'm not worried about which one is right at the moment, I want to focus on other things. I'll let others look into and confirm. I'll just take the species accounts dates for now.

With just 18 pieces of datum (datum = singular, data = plural) hard to get much more than a mean and a median. They match nicely at this point. Statistical analysis works better with more data, so I then went back a further ten years:

So, I was mean, and 'threw out' that 13th March record. Because, often in statistical analysis you need to throw out the highest and lowest. It's not about the truth of the records, it's to help focus on the trend; 'probability', 'variation', 'confidence', 'inferrentials' 'standard errors', 'normal distribution curves' all make my head spin.

But, to a thickie like me, 'standard deviation' sticks out, and that's all about quantifying the amount of variation, focusing in close the furthest data are from the mean. If do do something that will make statisticians wince, and ignore the first and last dates from my chart, this happens:

So why we also need a more sensible line of thought: "What do Cuckoos eat?"

-----

Looking at the species accounts in the annual reports I have, I tried another statistical analysis. I grabbed the first date, the second date, and then the date for the first multiple arrival. Of course, this is not robust: I have no access to the database to check the authors have included multiples, I'm just trying to show a trend:

Early arrivals. We might think we can say the run of early dates means something, but if we're not seeing early multiple arrivals, they're pretty much statistically insignificant (in the nicest sense).

And there's the beauty of BTO's Birdtrack; a big dataset focusing in on these larger trends. Why every birder should consider providing data to them.

I fear I might now have to have yet another go at reading 'Statistics for Ornithologists'. I think I'd find Klingon easier to pick up, I just hope this dummies guide might have helped some readers to think about data a little more.

Meanwhile, in the ornithological world, any early March Common Cuckoos, like their cousins from over the pond, those Yellow-billed and Black-billed Cuckoos turning up here in the autumn, are pretty much beggared. Why? "What do Cuckoos eat?".

-----

Caterpillars!

They love 'em. They adore 'em. They turn up and hoover 'em up. No point in getting here early. Not unless laying dates for host species and food sources move their dates dramatically. And this month, so far, hasn't been that good for hatchings. They turn to beetles in their absence. Now, how many of them have been active of late? How easy it would it be for a Cuckoo to find enough food? (Why that early March ringing record in BWP was described as exceptional. How had it survived?) No self-respecting Cuckoo is going to want to turn up early. The timing impulse to leave Africa is inbuilt; they can't tell what the weather is like here when they set off. They slow up when they near if they hit bad weather but, seriously, why would a Cuckoo want to race here just to die?

Why I don't focus on first dates any more, but try to learn more about behaviour and ecology. If you haven't learnt anything about statistics from these ramblings (and half-decent mathematicians will probably be groaning at my interpretations) then more likely you may not forget what a Cuckoo eats. So if you hear an early, or mid-, March bird well done and worth trying to get a visual...