The one visit to Larkfield I do remember vividly is the February trip that I cut short so I could race back to Rainham in time to carry out a Low Tide Count. I really can close my eyes and still see the Spotted Redshank I had that morning. Each to their own.

------

Typing that sent me scuttling off to the shelves for the count write-up in the 1989 Kent Bird Report. The more that things change, the more they stay the same.

As well as the February count, a second was made:

"..in September 1989.. all counts took place on weekdays.. when disturbance was slight, and problems with birds moving from area to area minimal."

"It is hoped that the numbered sections here, or combinations of them, will become standard counting units.. for the benefits of those involved in conservation planning, where data may be required for small parts of the estuary under threat.."

Of course, the areas weren't promoted well enough to birders to ever become established. Still aren't. The individual sector results gained from official estuary-wide surveys aren't actively publicised; data is data after all. Thirty years ago an employee of a second charity co-ordinated local WeBS results. One counter asked them to be put in touch with the counter next door so they could chat and see how things compared. Was told, in no uncertain terms, that wouldn't be happening because of data protection, and in fact much of the data gathered actually belonged to that second charity because they cordinated it. The counter was never told who was counting next door. Needless to say, they lost that particular counter.

Back then, as in recent years, co-ordinated counts were not the norm. At least the weekend vs. weekday differences in high tide roosting behaviours had been identified and highlighted.

Back in 1989 a second need had also been identified, to try to get some decent autumn counts as well as 'winter' (October to February). To look through the monthly totals in county Bird Reports up to my return in 2013, it would seem half-decent autumn species totals on the Medway were minimal. Wrong.

Yes I bang on. Often the reply I get is 'oh you have all the answers'. I really don't. I'm just well-read. Others found and published the answers at a county level nearly three decades ago.

-----

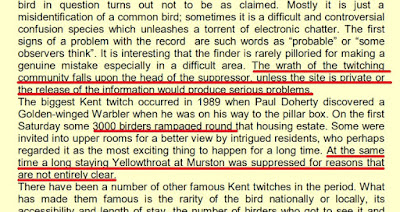

Of course, there's an elephant in my 1989 memory storage room, which needs highlighting for next, and the next, and the next generation birders to learn from. Twitter might have been filled with that Golden-winged Warbler this past week, birders on the sea wall have been talking to me about that Common Yellowthroat.

"The first county record of this American landbird involved a first winter male present at Murston from January 6th to April 23rd.."

To say this bird came to polarise locals is an understatement. The fallout between 'camps' led to the eventual demise of the informal 'North Kent Birders' group. No more social meet-ups down the Hastings Arms, no more attempts by the NKB to build local coverage, through efforts such at co-ordinated searches along eastern Sheppey. 30-ish birders out, ensuring full coastline coverage, looking for autumn migrants- great stuff, never since repeated. And some birders slowly switching off, withdrawing from the 'scene'. With a turn-over/reduction of WeBS counters in the years that followed haunting this estuary for years.

That (plus subsequent downers here in the following years involving birds I'd never even seen or invited to) helped me reach a decision more than a dozen or so years ago; I would never 'see' a county scarce or rare, again.

By that I meant not only I wouldn't see other's finds, but also I would never bother 'self-finding' anything again. Sniff of a rare? Turn around and walk away. They really are just not worth it. The inflated values put on them devalue other species, ones that need greater worths recognised.

And before you ask, nope, I never saw the Yellowthroat. I suspect if I had done, it might well now be just like that Golden-winged; wiped clean from my memory banks as 'just a rare'. So many of the birds I twitched back then are gone from the memory bank.

And nope, I didn't even hear about it for ages. Was told about it in a phone conversation with one of the observers, several months after it had left. We had been talking about something completely different. At the end, they raised the subject, they felt I should know, but they were clearly still worried about reactions they were getting. So they were amazed that someone could take it well as I then did during that conversation; I just congratulated them, and stressed I had no problem over it; I could see from their perspective they had acted well within the Birdwatchers' Code of Conduct. It was just a bird.

Fast forward 29 years. One seawall conversation this past week went on about how the Yellowthroat 'killed' North Kent Birding. I can agree with that, partly. (It wasn't really the Yellowthroat's fault.)

The other comment I got was the tired old 'and I really should have been allowed to see that bird' rant. I explained that since that Yellowthroat the Hubble telescope had been launched and helped confirm the universe doesn't revolve around their life/county list (with a real life smiley face of course).

Postscript:

Six months later, and the County newsletter is seemingly warming things up for the 30th anniversary. Oh I do love it when the author has already supplied the answer to their inferred question. (And even I wouldn't ever claim there was a 'rampage' on the streets!)